Rattlesnakes, rabbits and rollercoaster-riders all have an autonomic nervous system: that is the part that keeps your heart beating and causes you to blink when a fly is about to hit your eye. Whilst much of this nervous system serves each group similarly, the really interesting thing is that each of these groups use this nervous system very differently.

Indeed, if you have ever taken a look around the reptile enclosure at a zoo, you’ll be lucky to see one of the reptiles do much more than barely move. They are behaviorally-challenged exhibits. Notice there’s never usually a flock of snakes or a swarm of iguanas: reptiles are not known for their pack mentality. And you’ll be conscious of the fact that, in the reptile world, herbivores are rare; and bigger reptiles tend to eat smaller ones, regardless of whether lunch is a member of their own species.

Accordingly, the reptilian safety strategy – a subset of their overall survival strategy – has adapted to rely on solitude, camouflage and stillness. Looking and behaving like it is not really there, by looking and behaving like something that isn’t actually alive. It works wonderfully: as with the fascinated public at the reptile enclosure at the zoo, most inquisitive seekers of sustenance are effectively changed into passers-by, as there’s little to look at. But, if the solitude, camouflage and stillness doesn’t work well enough on occasion, or when something gets to close for comfort inadvertently, the next survival strategy is to become highly aggressive, suddenly and convincingly, or to beat a rapid retreat. This is all the autonomic nervous system kicking in. And just as with the heart beating and fly-induced blinking, the animal makes no conscious choice in any of it. Rather its body simply reacts to the situation.

By contrast, if you are considering buying a mouse at a pet store, it is a behaviorally-rich event and you’ll be lucky to see one that’s not in motion. And it is extremely unlikely that the mice would be stored one-mouse-per-cage. Rather there will be umpteen mice in a cage; all of which will be hyperalert, hyperactive and interacting with one another in a fairly non-aggressive fashion. The safety strategy of mice is cooperation through group hyperawareness of, and rapid movement away from, any external threat. This is a very typical mammalian pattern: think meerkats or zebras or hyenas on the approach of a large male lion. Again, the animal makes no conscious choice as to its behavior in the face of threat, its body is simply reacting to the situation.

Social mammals receive safety, as well as other survival and reproductive benefits, from being in close proximity to others. To realise those benefits, they have had to adapt and suspend the previous proximity-trigger to attack or retreat from others who are one of them. That behavioral adaptation occurred via a change in the structure of the autonomic nervous system.

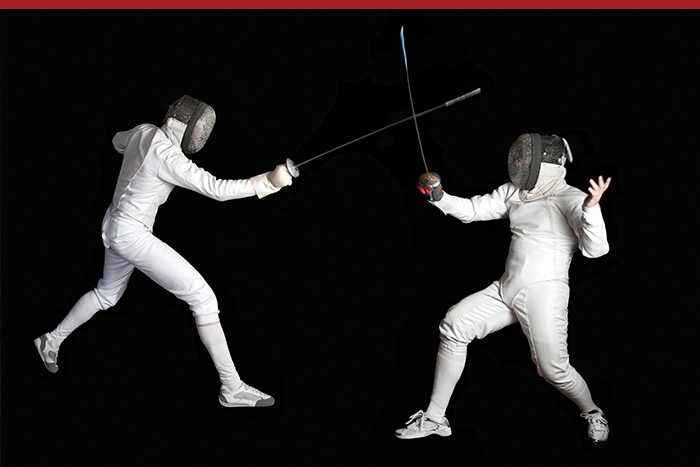

Specifically, mammals evolved a secondary branch of the Vagus nerve, which enables mammals to apply a brake, as it were, to their fight or flight responses. At the same time, when there are territorial or mating-right disputes, this vagal-brake is released and the fight-flight response is free to activate for a threat from within the group. It is fairly common for such competition by force to be non-fatally settled because of the value placed on group members when not in competition, which is most of the time; with the loser conceding defeat by either submission or retreat.

This understanding of fight, flight or immobilization tied to the Vagus nerve is the subject of much study across a range of issues in recent years, including disorders such as PTSD, eating disorders, depression and its links to the human biome. It has been studied and promoted by Stephen Porges from Indiana University and University of North Carolina.

Now, as interesting as all this is, what is truly fascinating is that, when a mammal is attacked or threatened, the mammal ‘shuts down’: its heartbeat, breathing and blood pressure all drop measurably and dramatically; and it exhibits no behavior at all. The mammal becomes as still as a reptile because the reptilic vagal response has been triggered. And, even more enthralling, whilst the physiological life-signs plummet, the animal’s brainwave activity remains at the former sky-high level. As such, if the cheetah lets go of the limp gazelle, the gazelle will spontaneously and rapidly scramble and run. Just as before, the animal makes no conscious choice to ‘shutdown’ nor rapidly beat a retreat, its body is simply reacting to the situation.

So, my fellow mammals, how does all this relate to the most sophisticated and successful of all mammals and high primates that constitute “us”?

Have you ever come across someone whom was much more powerful than you and you just found yourself being noticeably quieter? Has there ever been someone with whom you always seem to be butting heads? Have you ever become nervous of the reception you might receive when you had to bring really unwelcome news to an authority figure? Have you ever choked during that ‘big career-building presentation’? Have you ever surprised yourself by a sudden lost temper over a relatively small issue? Have you ever woken up feeling worried or anxious, with no real knowledge of what was actually making you feel like that?

Alternatively, have you ever performed at your best effortlessly and for no particular reason? Have you ever been at a social event and just found that the conversation really flowed inexplicitly well? Have you been surprised that a networking event went unusually well and that everyone you met was really engaging to you and they seemed to be really engaged by you? Have you ever had a big-ticket sales presentation or a high-stakes negotiation and where, despite the facing challenging issues, both sides just clicked and enjoyed the very process of achieving the agreement?

Whether you find that you are in a fight, flight, freeze or flow state, the science is clear: the Vagus nerve chooses the state!

This nerve has a profound effect on the quality of our subjective experience, in all aspects of our lives. It is core to what we can do to improve our cognitive and social intelligence; as well as regain, increase and sustain our enjoyment of our private and professional lives.

So, whether you are a Member of a Board of a multinational corporation or the production manager of a large complex manufacturing site, a sales manager or an operator at a mine site, a parent or a teacher, a soldier or a police officer, a negotiator or a salesperson, someone’s leader or someone’s lover, understanding how to create a deep sense of safety inside your own neurology and, by doing so, create effective safety conditions for others’ neurology, is a gift that keeps on giving. We will explore in a later piece how to use this knowledge of the Vagal nerve and its function in triggering so many of our seemingly automatic responses to people and situations.