The airline attendant greets you at the door of the aircraft, with a warm smile and says welcome aboard. Throughout the flight s/he is pleasant, attentive and responsive. As a passenger you have no idea of their trials and tribulations, nor for that matter do many of their airline colleagues.

Nor would you expect to know such things. The person is “in role”, as are each of their colleagues and the flight crew together operate as a team. They have a job to do. So it is with teamwork. When you are a member of a team you contribute not only to the joint task but you do so in role as a team member. And you do this no matter your personal temperament or the life issues with which you may be dealing.

High performing teams in manufacturing plants, mine sites, hospitals, professional service firms are no different. Invariably they are well formed and high functioning, they have the relationships and ways of working that allow them to be so. And well-formed teams have certain characteristics including active participation and contribution from all members with one another and to the task. But teams can’t form without this participation.

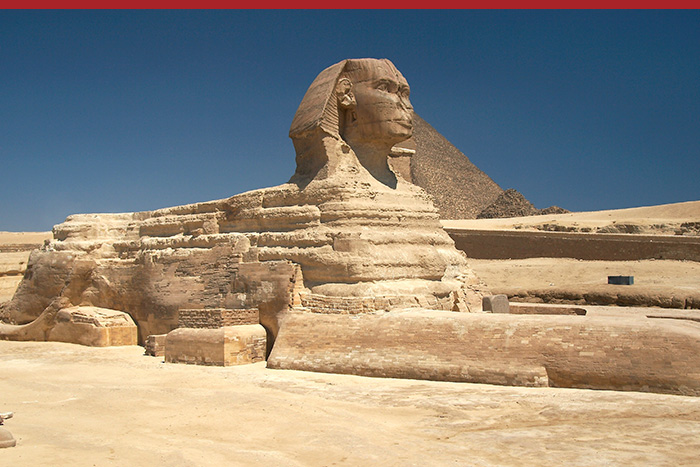

A non-contributor stops the team performing, by preventing group formation. At a recent senior management workshop of about 15 people we were confronted by someone who simply did not participate. Throughout the two-day event, this person moved very little, said virtually nothing (despite many attempts to elicit participation and movement), had a blank face, and spent a lot of the time with their pupils dilated, “inside” their head. They behaved in the manner that our friend and colleague Michael Grinder calls “the sphinx”.

When confronted by the facilitator, the person concerned claimed to be an introvert and therefore had a bias against very active group participation. Whilst this may have been true, the simple fact is this person’s extreme silence and stillness stopped the group forming and thereby stopped the group becoming a team. Groups cannot form, teams cannot become high performing if one of their members is a sphinx.

In another recent meeting of a work group three members participated little for they too claimed to be quiet and introverted personalities. That team had equal difficulty becoming formed and ultimately high performing.

These cases raise the question about under what circumstances are my personal characteristics allowed to limit the formation and hence performance of a team. When is it OK to hold a team’s effectiveness hostage to my personal preferences? It seems to me there is a range of individual human behavior arising from our “person” that all human groups and teams can accommodate without limiting their effectiveness, but the one characteristic that makes it very, very difficult is extreme silence and stillness. A sphinx in a group represents such an extreme.

Like the airline attendant no matter how each is as person, as a passenger you expect them to be in role and contribute to your journey as a member of a flight team. Michael Grinder points out that back in the 60s there was a bias to seeing the answer to effective organizations in relationships among their members. By the 90s this bias had swung to seeing effectiveness in clear roles and accountabilities. He calls this swing one from person orientation to position or role orientation. We now see that both are required. It is not person or position, but both. By having a relationship with you as a person we can work together effectively from position, in role, and I can hold you accountable.

Being part of a high performing team, a well formed and high functioning group of people, requires both effective relationships (person) and effective contributions (position) and claiming introversion as a reason for non-contribution simply doesn’t cut it.

The team leader faced with a sphinx as a group member has a particular problem. There are two interventions at your disposal – firstly, request them to undertake a task that requires them to move around the room, e.g. hand out papers to their colleagues, be a scribe on the flip chart, etc …. Any movement by the sphinx will allow the group to form a little more and for the team to function a little better. If that fails and sphinx persists, then you will probably have to take them aside and, after checking there is not some factor that you’re unaware of, then point out to them that work of the team requires their active verbal participation. Failing this, the team leader then has a deeper issue to address about the sphinx’s future membership of the team.

Tim Dalmau