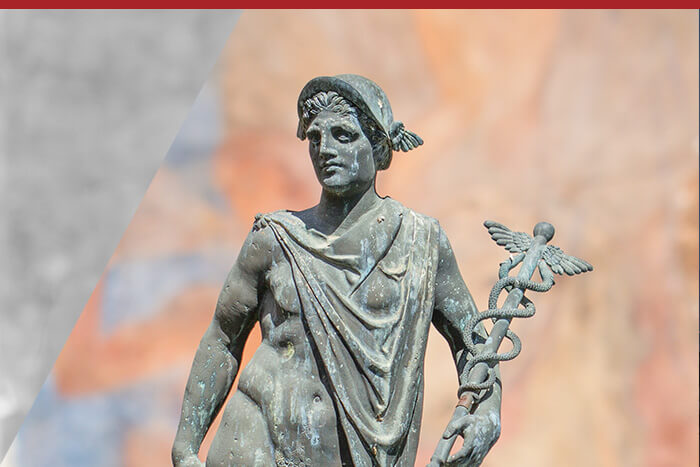

Hermes: the networked organization

Hermes was the most popular of the gods. He was the god of travellers and messengers, heralds and liars, shepherds, thieves, merchants and scholars. Like other Olympian gods, he was the amalgamation of several more ancient deities, but he appears in classical times as a very distinctive character. He is a very slippery god, an opportunist without any respect for conventional morality, a trickster, a con man and a thief. He flourishes in a climate of uncertainty. He is elusive, unpredictable and mischievous, and cannot resist any opportunity to make a profit on a deal. He is also very charming, and known to be particularly friendly to human beings.

In a Hermes culture there is considerable emphasis on the free transmission of information, but not so much attention to whether that information is worth transmitting. Flexibility and mobility are greatly valued. There is a great deal of attention to image, but not much concern whether the image bears any relationship to reality. The Hermes organization is dominated by the image of the marketplace, so that the only value given to any activity (or any person) is its exchange value. Students, patients, audiences, prisoners, even the deceased, all become ‘customers’. The Hermes organization is not very interested in actually producing anything. Its capacity to produce things is simply an asset to be bartered. Management is ‘content-free’; there is no expectation that people in leadership positions have any knowledge and experience in the particular areas that the organization works in, as long as they can ‘facilitate’ the activities of others. It may be easier in such an organization to advance through smooth talking and a shiny résumé than through loyalty or hard work.

Hermes is a very friendly and charming god, but he is not really trustworthy. The pathology of the Hermes culture often appears in a total lack of ethical sense. For Hermes, there is no essential difference between truth and lies, between honest and dishonest dealing. A Hermes-dominated management may be pathologically slippery and elusive, not only with regard to moral principles, but also with regard to goals and practices and the treatment of employees. It is impossible to pin such people down, because they don’t actually believe in anything. (Of course, this brings the advantage of infinite flexibility.) Their desire to see things from many perspectives and to keep all options open may make them incapable of making a decision. Their preference for image over substance may lead them to spend the organization’s resources on creating the illusion that something is being done rather than actually doing something. It also leads them to an extensive use of euphemisms like ‘right-sizing’ and ‘out-placing’ to disguise reality. When something goes wrong, they devote their energy to ‘damage control’ (by which they mean maintaining the appearance that everything is all right) rather than remedy the situation.

Hermes is inclined to be somewhat infatuated with his own cleverness, and Hermes-dominated organizations only too often are too clever for their own good. The organization taken over by Hermes will always be on the lookout for a magic solution: the last thing it is likely to be interested in is hard work. If it is not producing the results it wants it is likely to seek the solution in a ‘restructure’, and the pathology of Hermes is often seen in organizations which destabilise themselves by constant ‘restructuring’. Hermes has no interest in the past, and little in the future. All of his goals are short-term ones. At its best the Hermes culture is magical, exhilarating, constantly testing the limits of our inventiveness and flexibility; at its worst it is a culture of deception inhabited by amoral opportunists.

Many organizations in the advertising, marketing and sales industries have strong Hermes cultures, as we would expect. We are likely also to find Hermes cultures, appropriately enough, in the media and travel industries. Yet when a Hermes culture becomes dominant in manufacturing or agriculture, the results can be disastrous. To see this at work, we need look no further than the deep pressure CEOs feel to respond to marketplace demands for certain styles of management, certain elements of strategic intent and certain pathways of strategic direction. Gone are the days when a CEO was responsible to a Board alone for his/her performance. The marketplace, through the voices of analysts and financial journalists now demands of CEOs a responsiveness to the market’s short term imperatives for return on capital. This can place the corporate strategist in some very significant dilemmas, balancing long term good against the need to keep the marketplace hounds from the door.

For the past two decades at least political life has appeared to be dominated by Hermes personalities, and there is great pressure within institutions of all kinds to adopt Hermes culture. This is a source of great stress, as organizations traditionally dedicated to Demeter, Hera, Hephaistos or Apollo are expected to suddenly abandon their focus on care, service, crafting or research and become slick marketeers of these commodities.

An increasingly common and effective form of organization is the network. It is shaped by the Hermes images of unregulated communication, flexibility and the subversion of central authority (Zeus) and hierarchical structures (Apollo). It does not have anyone in charge. It has no premises, no temple of its own, but is dispersed over a wide area, its activity constantly shifting from place to place according to where communication is taking place. It is constantly changing shape. In conventional organizational terms it is slippery and groundless and lacking in appropriate boundaries. It does not even have an established membership list.

A key distinction between Apollo cultures and Hermes cultures lies in their attitude to uncertainty. Apollo cultures have little tolerance for uncertainty, and put a lot of energy into avoiding it. (Many of these ways consist of magical rituals disguised as rational administrative procedures.) Hermes cultures thrive on uncertainty. They love to live ‘on the edge’ and don’t value anything enough to be committed to maintaining it. A Hermes initiative within an organization dominated by the Apollo values of order, hierarchy and stability is likely to be perceived as a threat, and the guardians of Apollo values will make it their business to bring it into line, even while they talk Hermes-talk.

Yet for all of this, the Hermes fantasy of emergent self-organizing networks of communications lies at the very heart of so much new science that is finding its way into organizational and management literature.

The escalation of information technology has made it possible to entirely rethink our notions of organization in Hermes terms. The god of travellers is at particularly at home with the groundlessness of cyberspace and the motility of the information superhighway. Zeus clearly has his eye on the internet. Whether he will manage to get control of it is yet to be seen. It may be that its very nature will prevent it from coming under centralized, hierarchical control.

The consultant who approaches an organization from the perspective of Hermes will be much more interested in the process than the content. How flexible and adaptable are the members of this organization? How open to change? How ready to improvise? Where are they ‘stuck’ and how can they be rescued from their ‘stuckness’? How free is the flow of information? How well do they market themselves, and how skilled are they at persuading people to desire and buy what they produce?

Tim Dalmau