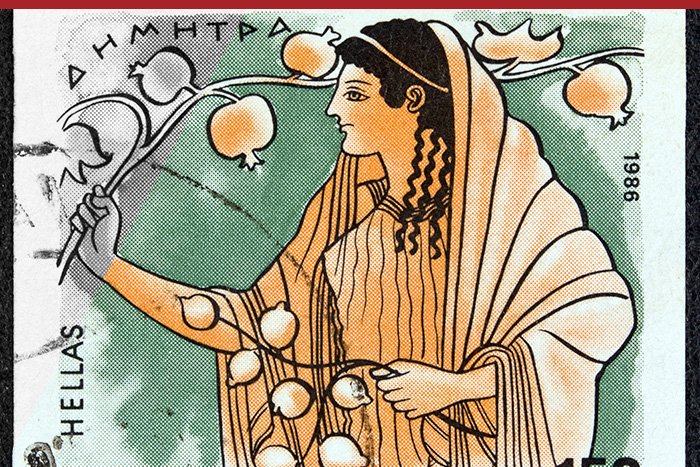

The organization with a strong Demeter culture takes mothering seriously. Central to its image of itself is its task of providing a safe and supportive environment for its members. It must look after them, as a mother does. It undertakes responsibility for the care of its members and sees this as essential to its nature. The executive exercises the power of the carer and nourisher, rather than the power of the bully or manager. Mother Demeter says, ‘Trust me. I know what is best for you.’ For their part the members or employees are content to be looked after; they even take it for granted, seeing it as the organization’s duty. Efficiency and productivity are not usually central concerns of the Demeter organization. The Demeter organization will continue to look after its children even when they are not financially viable!

The Demeter organization provides what Jack Gibb calls the ‘benevolent’ environment (Do this because I love you!), which he contrasts both with the ‘punitive’ environment (Do this or I will punish you!) and the ‘autocratic’ environment (Do this because I say so!). Demeter-power is still power, though it generates dependency rather than fear. For Gibb, benevolent power relations are a stage in the evolution of organizations from structures dominated by fear to structures in which everyone is empowered and free to realize their personal and collective potential. If Demeter really loves her children she will let them grow up[i].

The Demeter organization may make strong demands on the trust of its members. …. Demeter is not interested in consultation or participative decision-making, nor in rational management structures. If you accept the notion that mother is always right, if you love mother as mother loves you, she will take care of your every need. If you are not a good child, if you bite the breast that feeds you, she will withdraw it. There is plenty of room for the pathology of dependence in the Demeter organization. The members may be unwilling to grow into adults, and the organization may be unwilling to let them. Mother may care or abandon, nourish or deny, give birth or devour.

The traditional Japanese company is often perceived as a Demeter culture. The company holds all its employees in an enormous embrace, and they remain fondly her children, spend their lives in her embrace and gladly make whatever sacrifices she demands. Many government departments in other countries have traditionally been dominated by Demeter, with employees happy to give up personal ambition and the thrills of freedom in order to feel safe with mother. The situation is changing, however, with such departments now being taken over by more fashionable gods. Community organizations are also likely to have a dash of Demeter in their make-up.

Organizations inflated with Demeter become very safe places for those who value safety and predictability. Uncertainty is generally avoided. However, there is a significant price to be paid. One large corporation with whom we work a great deal is often described in the following terms ‘We may resent the company, but you have to admit it does look after us’. This company offers its employees an extremely generous health plan, more than ample relocation expenses, strong family support systems for expatriates on assignment. It also has a history of negotiating quite satisfactory deals with unions in claims cases. These things do not go unnoticed by the employees and it is true that, when questioned, they will (far more often than not) speak of being cared for by the organization. But the pathology of Demeter is a smothering dependency, and this in turn breeds passive aggressive responses – even outright irrational rage. Demeter feels the utmost dismay and bewilderment when things get to this stage, and cannot understand how her children whom she has nurtured and protected can be so irrationally ungrateful. In this organization, it is not unusual for senior executives to experience this dismay and bewilderment as they ‘cop’ the resentment and anger from their workforce that they have genuinely sought to nurture and protect.

The Great Mother, of whom Demeter is one personification, has a double aspect. On the one hand, she nourishes, cares and contains. On the other she smothers, devours and destroys our individuality. Murray Stein points out the risks of projecting this archetype onto an organization.

A well-run, consciously-managed organization – if there be such a thing – would attempt to ameliorate the negative side of this archetype by setting limits on involvement, which would protect its members from being overinvested and devoured. Because members of these organizations project the great Mother upon them and then become so dependent and so look to them for the very basis of material life and comfort and sustenance, the power held is enormous. This is especially true in a materialistic, non- or anti-spiritual culture such as ours is. Beyond rational considerations, it is felt that the organization controls life and death. To be banished from one of them is to starve and collapse into an abandonment depression. The base of support for the ego’s existence in the world is threatened. So tied into organizational life can the individual become that the self seems at stake, the core of the personality at risk. Promotion comes to mean self-esteem and life; demotion, abandonment and death.[ii]

The consultant who approaches an organization from the perspective of Demeter will be most impressed by the way an organization looks after the interests of its members. He will assume that any business that genuinely cares about its employees will be a business whose employees will repay this concern through their reliability and their willingness to make sacrifices.

[i] Gibb, J. (1978). Trust: a new view of personal and organizational development. Los Angeles: Guild of Tutors.

[ii] Stein, M (1992). p. 4. Organizational life as spiritual practice In M. Stein & J. Hollwitz, Psyche at work. Wilmette, ILL: Chiron Publications.

Tim Dalmau